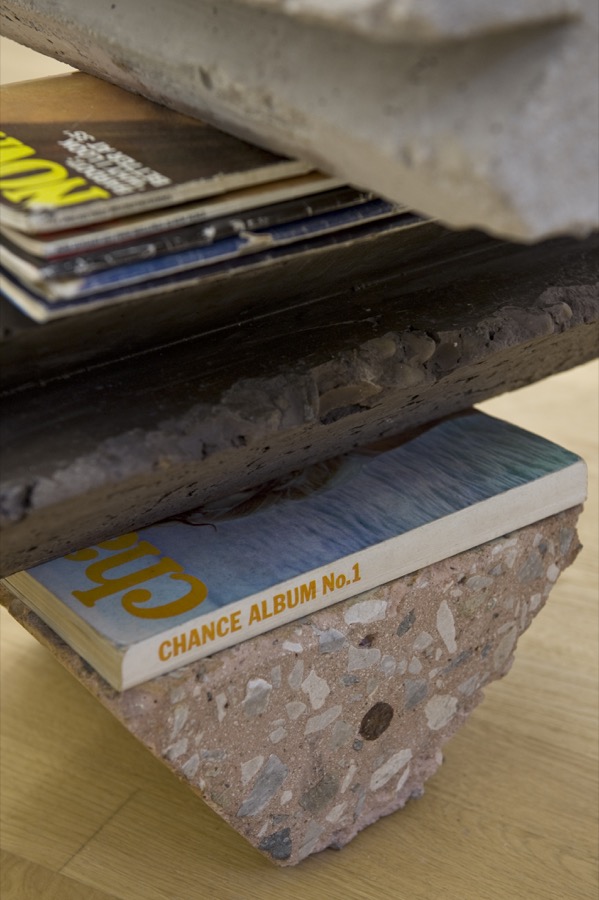

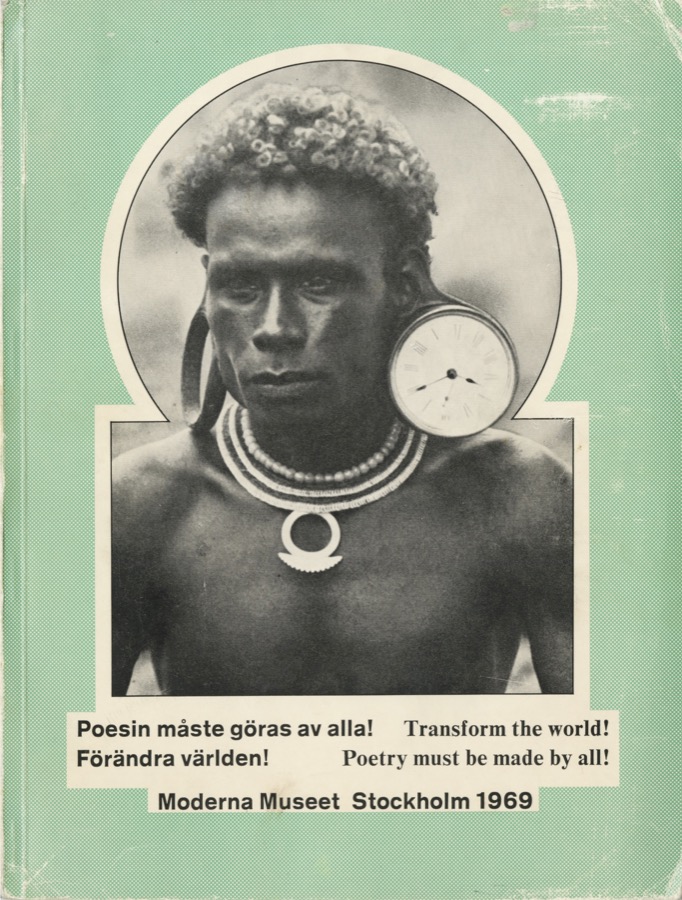

Escanografías vol.I-II, 2010-2011

June Crespo, Escanografías vol. I-II,

2010-2011, CO-OP ediciones,

texts Peio Aguirre

36pp each, 31x22cm

Into a Halted Exercise, Sarah Demeuse

EN/

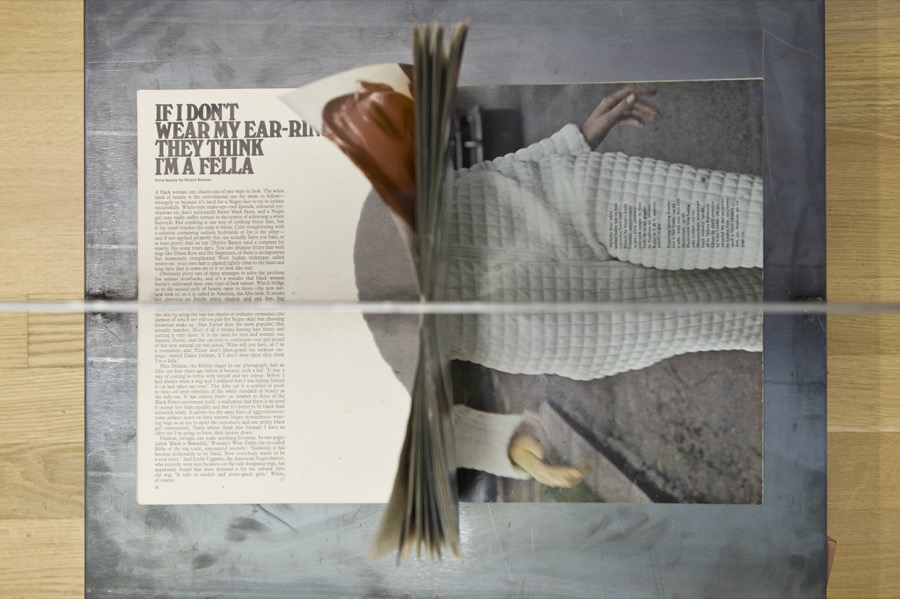

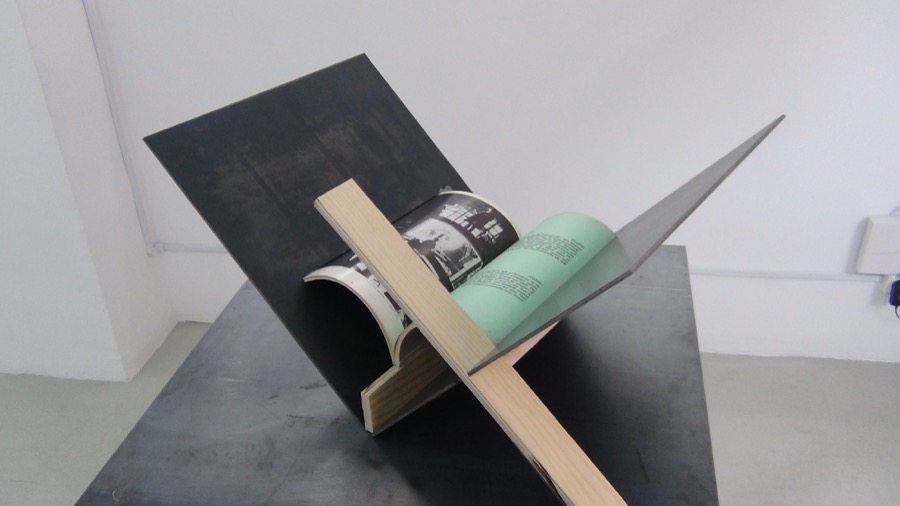

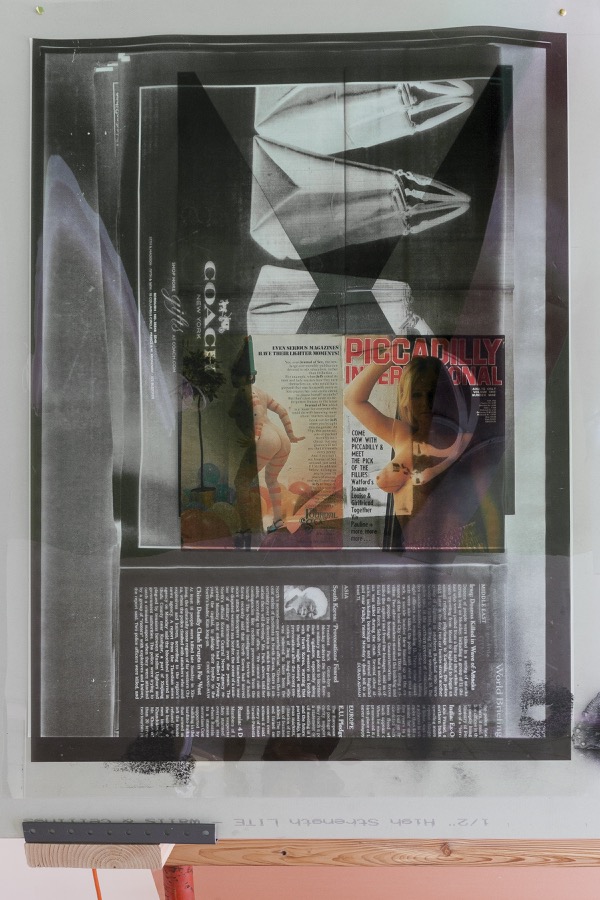

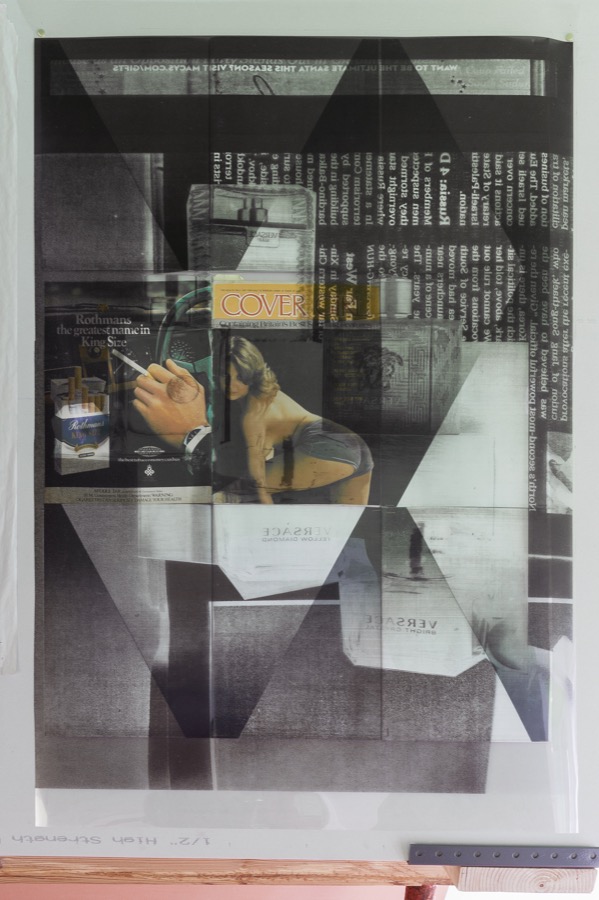

Two newspapers are pressed against the wall underneath a piece of wood. It’s as if the wood couldn’t touch the wall directly; with the papers adding a seemingly functionless and improvised element to the logic of construction posts in the street. Read this same story the other way around, and you find newspapers suspended between a wooden block and a wall. An intricate scaffolding system holds them in place.

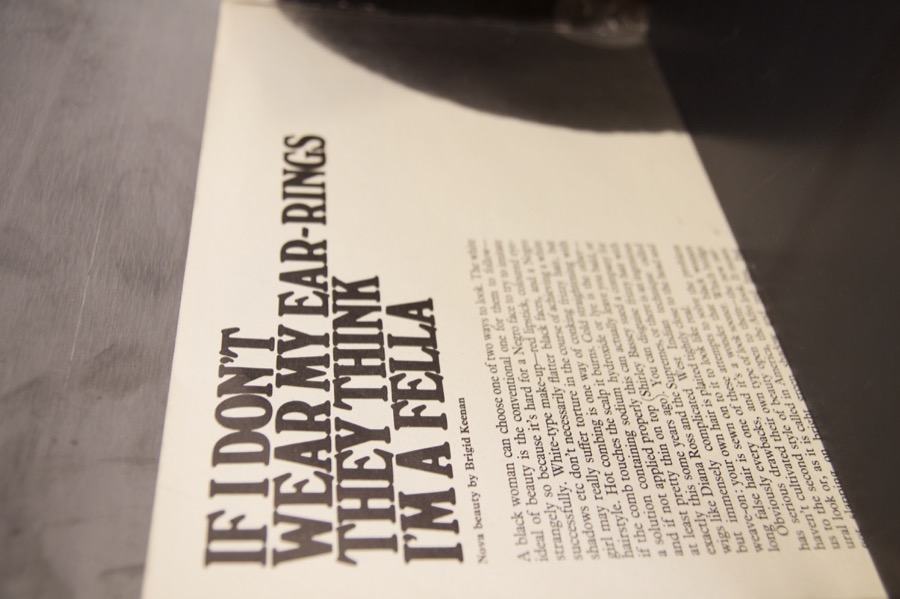

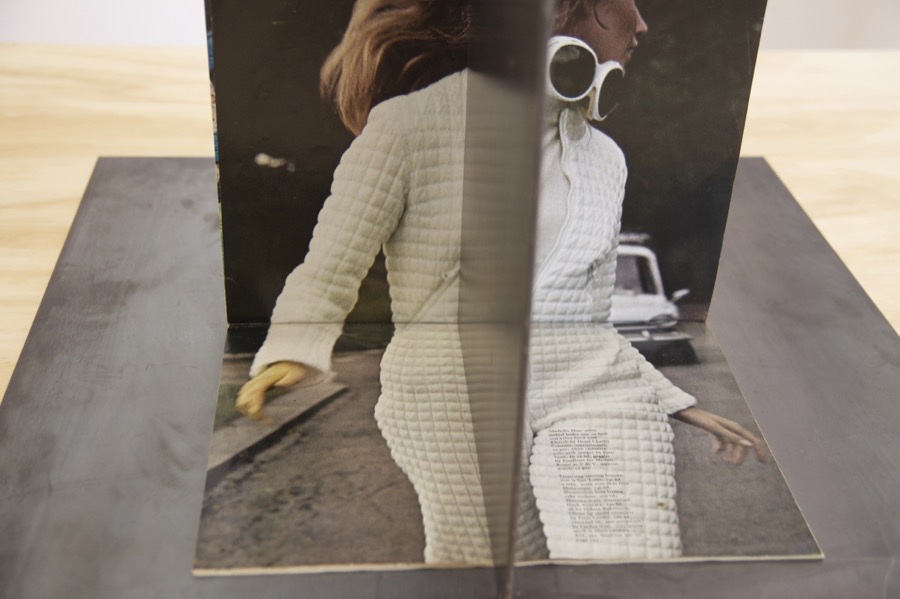

This apparatus made of shoring posts, wood wedges, cinderblocks and inserted vintage printed materials (a Vogue from 1979, or a 1970s Guide to Sex pocketbook) serve as support for the newspaper layering. But it also operates as a viewing machine that claims its gravitational presence. It does double duty as, on the one hand, sculptural support and, on the other, as self-standing material entity. Slicing parts into surface, infrastructure, support or adornment doesn’t make much sense in this assembly of materials, references, and printing techniques (which also stand in for different technical times). Everything could be data, everything could be raw material, everything could be function. It’s matter of temporary positions on the endless web of production.

While she is undoubtedly part of a post-digital generation and also formed by the strong artistic context of Bilbao, June Crespo acts like an editor in the most serious meaning of the term: her repeated assembling of new and already used work or materials, her folding, inverting positives and negatives, code and wood, noun and pronoun, work through timely questions that conflate medium and message, representation and appearance. They even suggest such binaries are no longer, or never were, valid. Her queries informed by modular thinking and ready-at-hand industrial formats insert one, like a frozen computer screen sometimes does, into a halted exercise, a moment in which mediums-in-production meet, mess and meddle.

Sarah Demeuse, curator, Rivet’s co-founder

ES/

Dos periódicos están comprimidos contra la pared bajo un trozo de madera. Es como si la madera no pudiese tocar directamente la pared; las hojas de prensa añaden un elemento aparentemente improvisado y sin una función determinada a la lógica de los postes de construcción urbana. Pero si leemos este relato en sentido contrario, nos encontramos con unos periódicos suspendidos entre un bloque de madera y una pared. Un complejo sistema de andamios los sostiene.

Este dispositivo compuesto de puntales, cuñas de madera, bloques de cemento y materiales gráficos vintage insertados (un ejemplar de 1979 de la revista Vogue, o una edición de bolsillo de los años setenta de Guide to Sex) funciona como soporte para unas capas de periódico. Sin embargo, actúa también como un instrumento de visión que reclama su presencia gravitacional. Cumple entonces una doble función: por un lado, se trata de un soporte escultórico y, por otro, es una entidad material autónoma. En este emsamblaje de materiales, referencias y técnicas de impresión (que representan a su vez diferentes periodos históricos) no tiene sentido alguno tratar de separar sus partes en superficie, infraestructura, soporte o adorno. Todo podría ser información, todo podría ser materia prima, todo podría ser función. Depende de la posición temporal que ocupan en la red infinita de producción.

A la vez que June Crespo pertenece indudablemente a la generación post-digital y se forma dentro del sólido contexto artístico de Bilbao, actúa como un editor en el sentido más serio del término: su asemblar continuo de obras o materiales nuevos o anteriormente utilizados, sus pliegos, invirtiendo positivos y negativos, código y madera, sustantivo y pronombre, giran en torno a preguntas relevantes que confunden medio y mensaje, representación y apariencia. Sugieren incluso que estas dicotomías ya no son, ni nunca fueron, válidas. Sus investigaciones, moldeadas por un pensamiento modular y elementos industriales corrientes, nos insertan, del mismo modo que a veces lo hace una pantalla bloqueada de un ordenador, dentro de un ejercicio interrumpido, un instante en el que los elementos del proceso de producción se encuentran, se desordenan y se inmiscuyen.

Sarah Demeuse, comisaria, co-fundadora de Rivet

June Crespo’s Scanographs, Peio Aguirre

EN/

June Crespo’s Scanographs

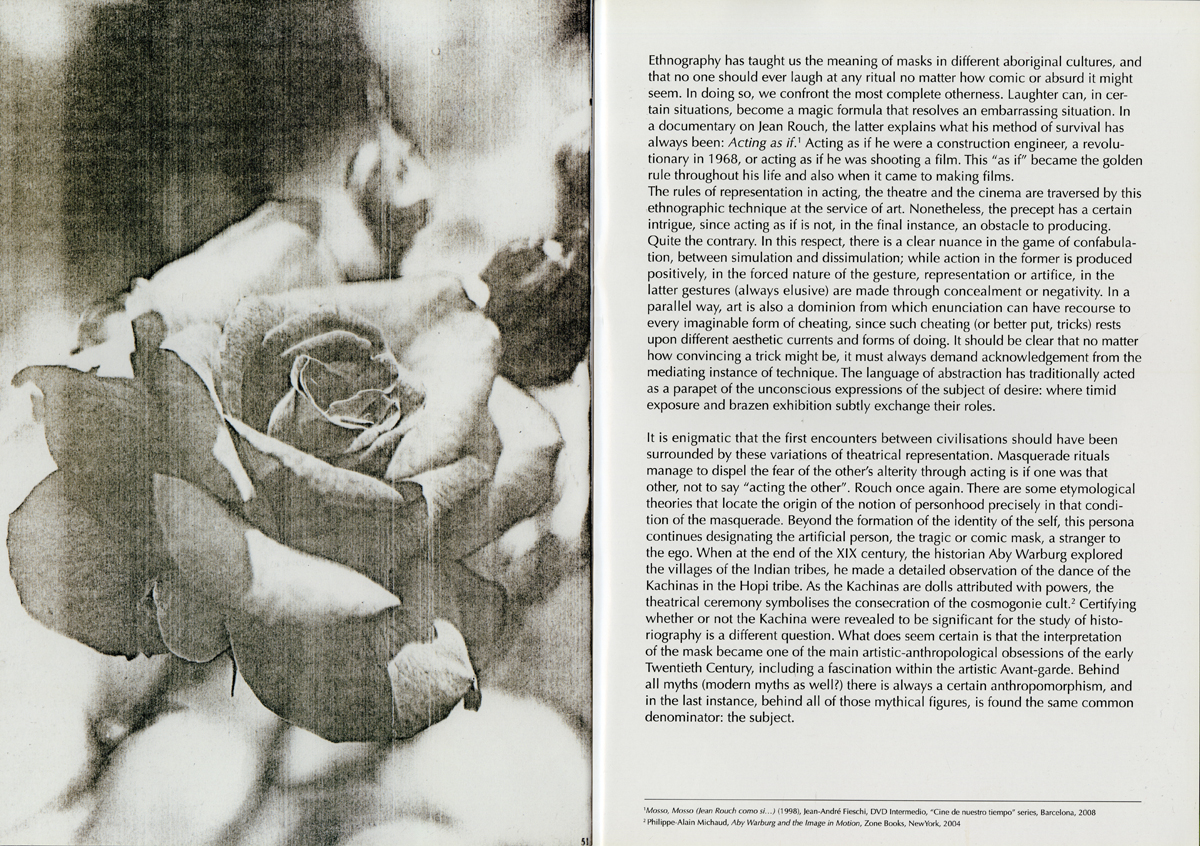

The revolution provoked by the discovery of a new technical advance remains controversial for many decades, without there being a complete dissipation of the polemic that at its inception threatens what was, until then, perceived as tradition, no matter how much the passage of time might bring about acceptance of that advance by the majority. At the start of the XX century photography and cinema were a living reflection of this situation in their conception as new tools of expression for the avant-garde.

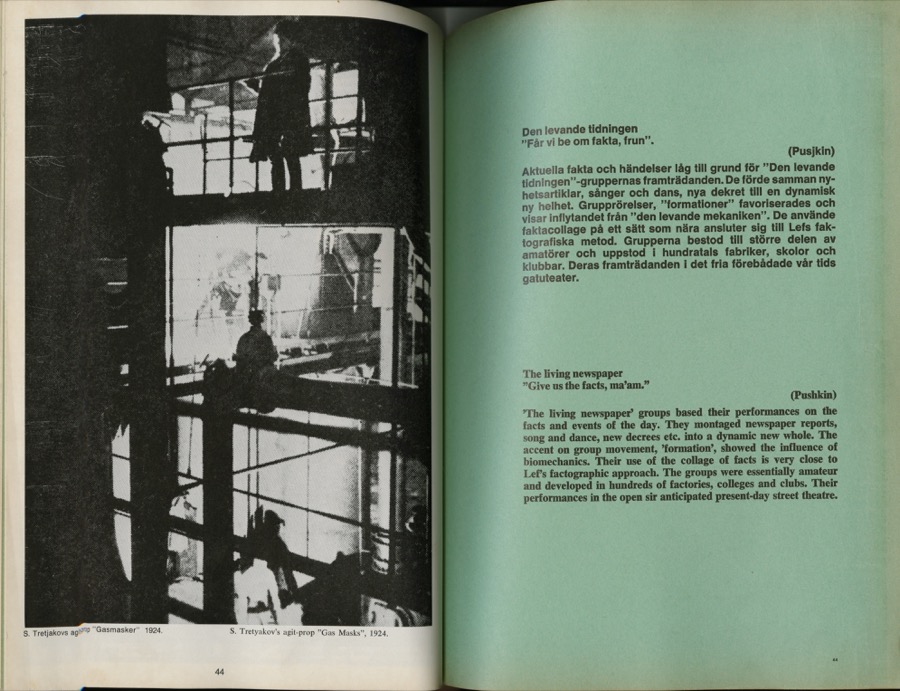

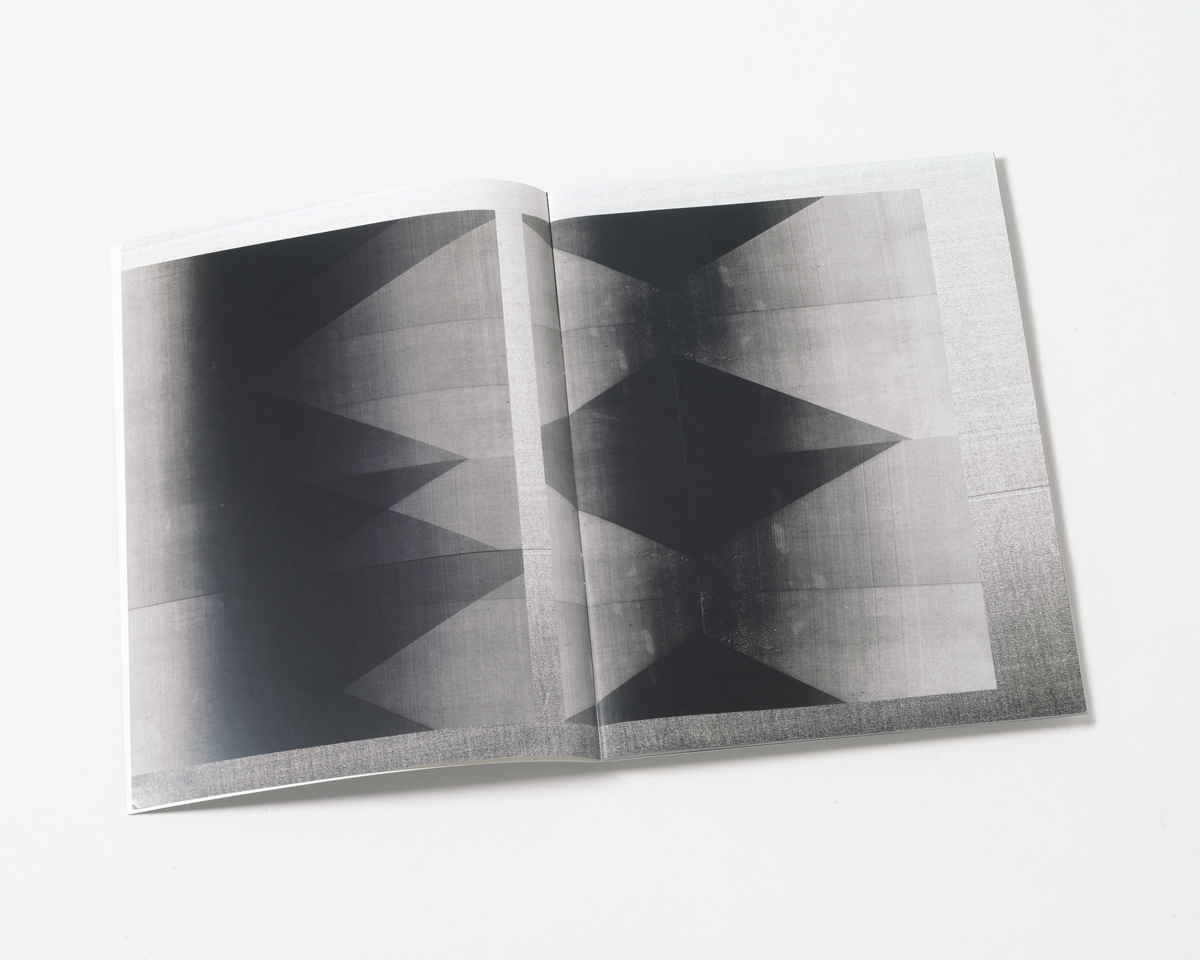

We are indebted to László Moholy-Nagy for having pushed the limits of the photographic medium towards a new existence. In his book Painting, Photography, Film, Moholy-Nagy described the concept of “photoplasticism”, which played a determinant role in the elaboration of his photomontages. He offers the following explanation: “it is a question of connecting different photographs, of a methodical attempt at simultaneous representation: the superimposition of word game and visuals; a strange and disturbing fusion, at the imaginary level, of the most realistic imitative procedures. Because at the same time they can narrate something, be solid and concrete, truer than life itself.” He equally applied this ambiguity between abstraction and figuration in his photograms (or photographs without a negative), made directly by placing everyday objects on an emulsified surface and their subsequent exposure to light, thus inaugurating new plastic effects between photography and painting.

Nearly one century later, the evolution of technology in history and in modernity warns us that trust in progress is not a blank cheque to be distributed anywhere as if it were a tranquilliser. But, besides that, the reproducibility of the technical image has not ceased to be the touchstone to which artists of different generations have returned time and again; from the first conceptual work that made use of the photocopy (Xerox) by Mel Bochner, Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed As Art (1966), to the recent ultra-postmodern neo-appropriationism of Seth Price or Wade Guyton in their exploitation of the possibilities of the graphic arts.

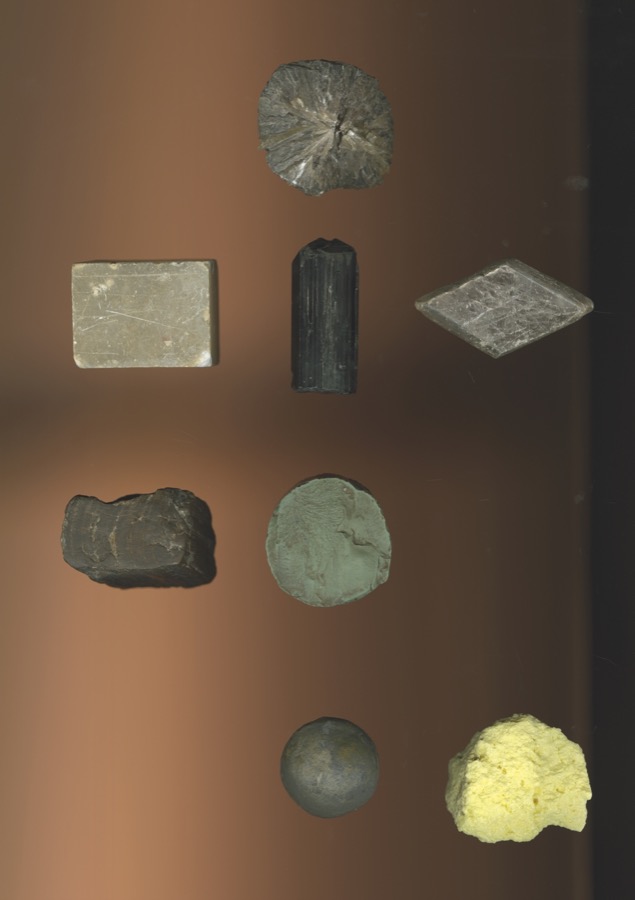

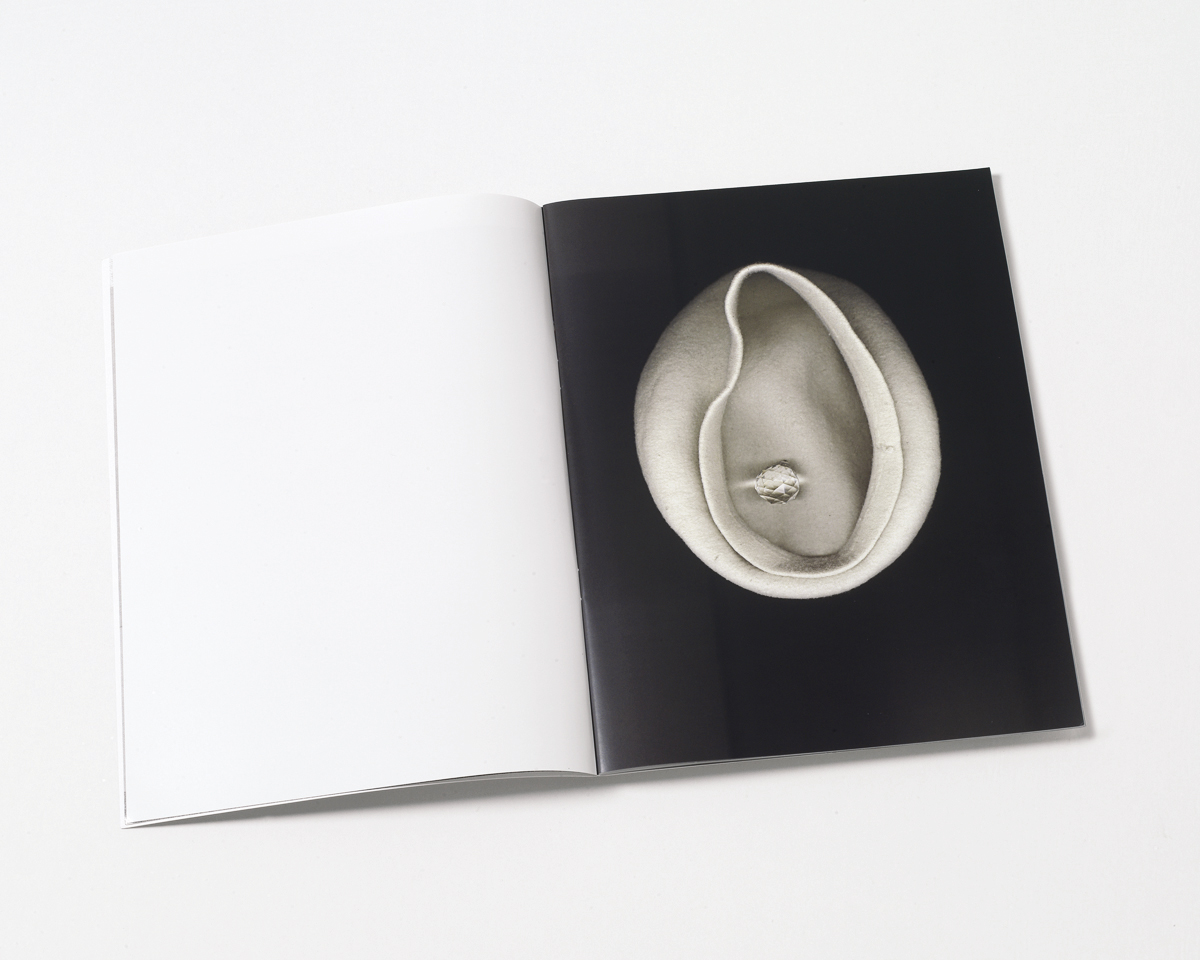

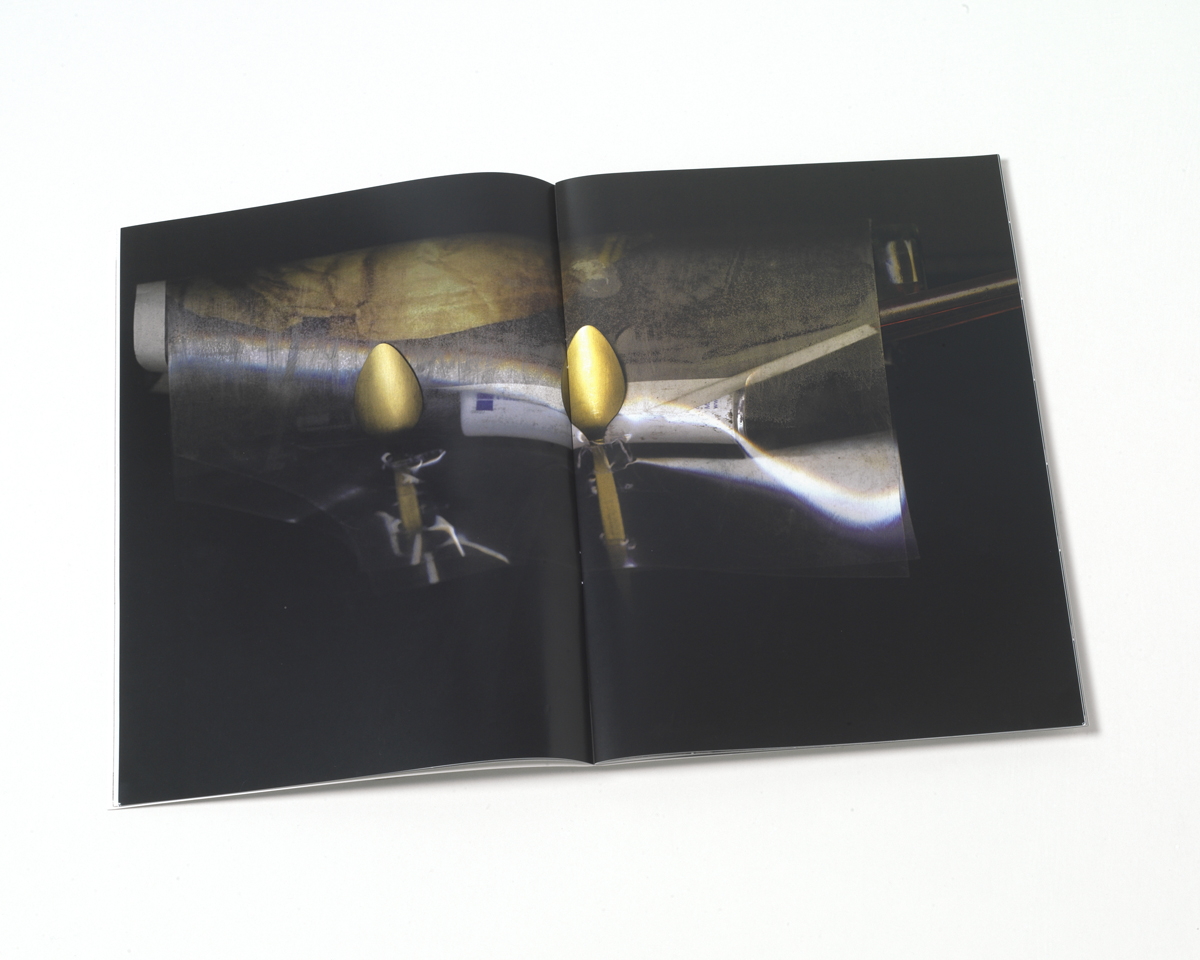

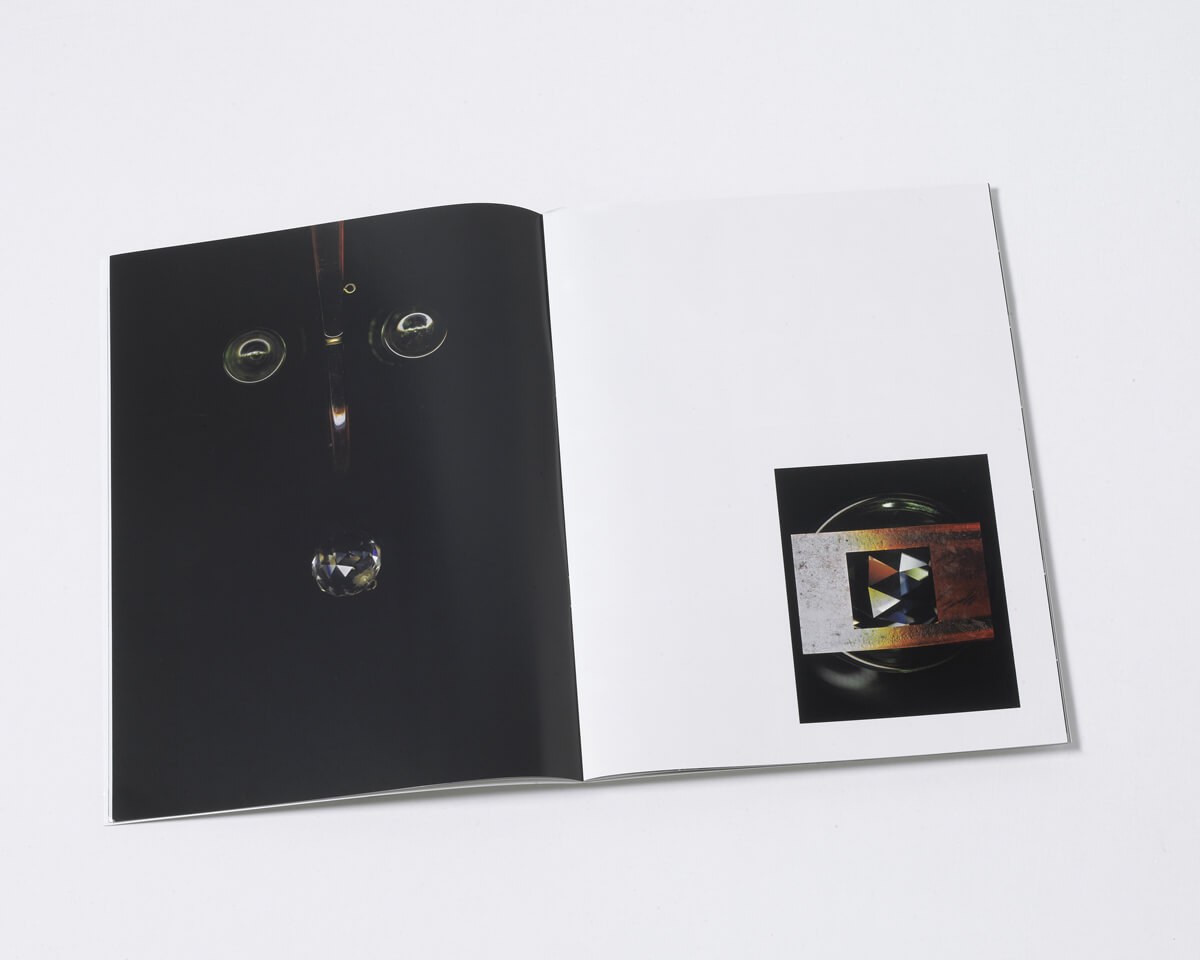

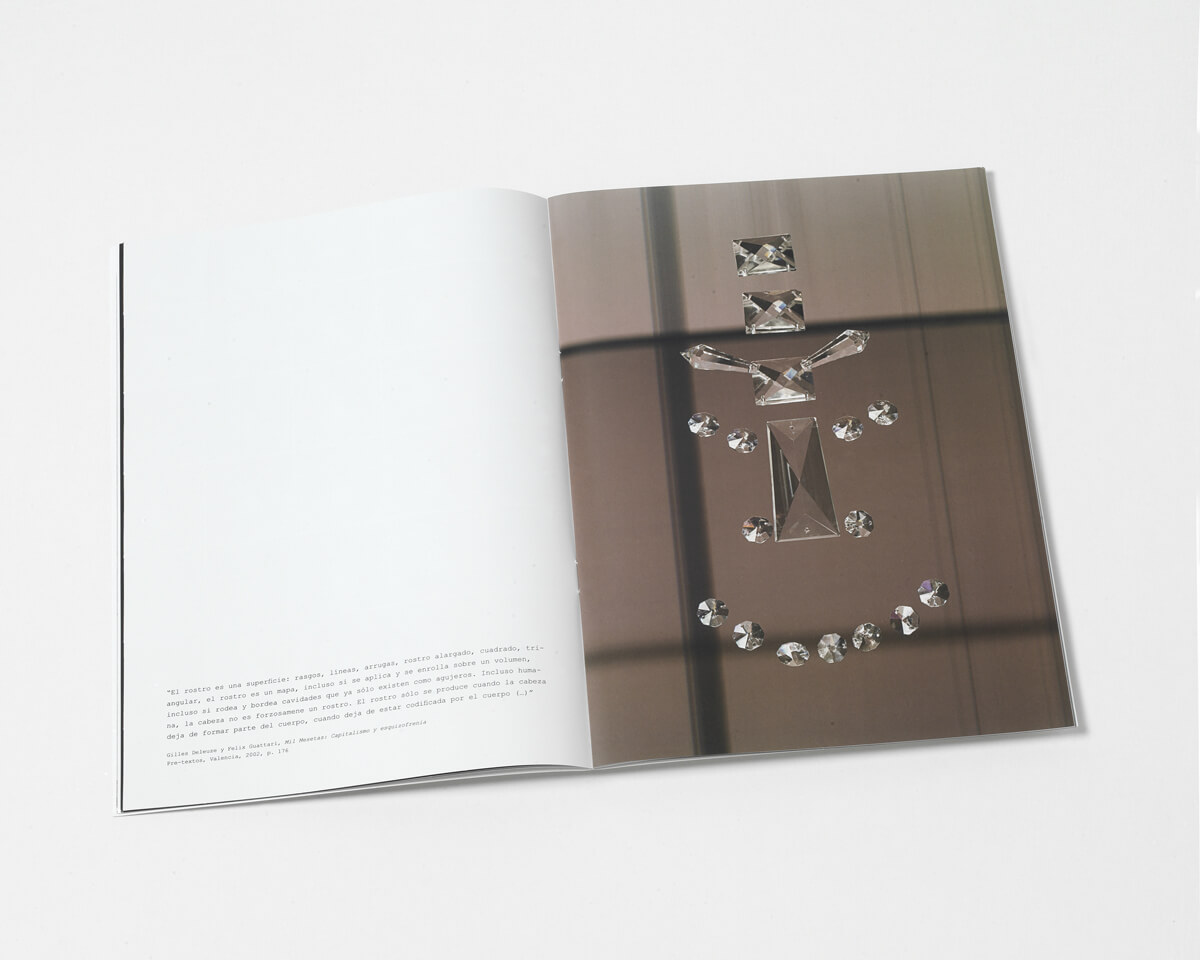

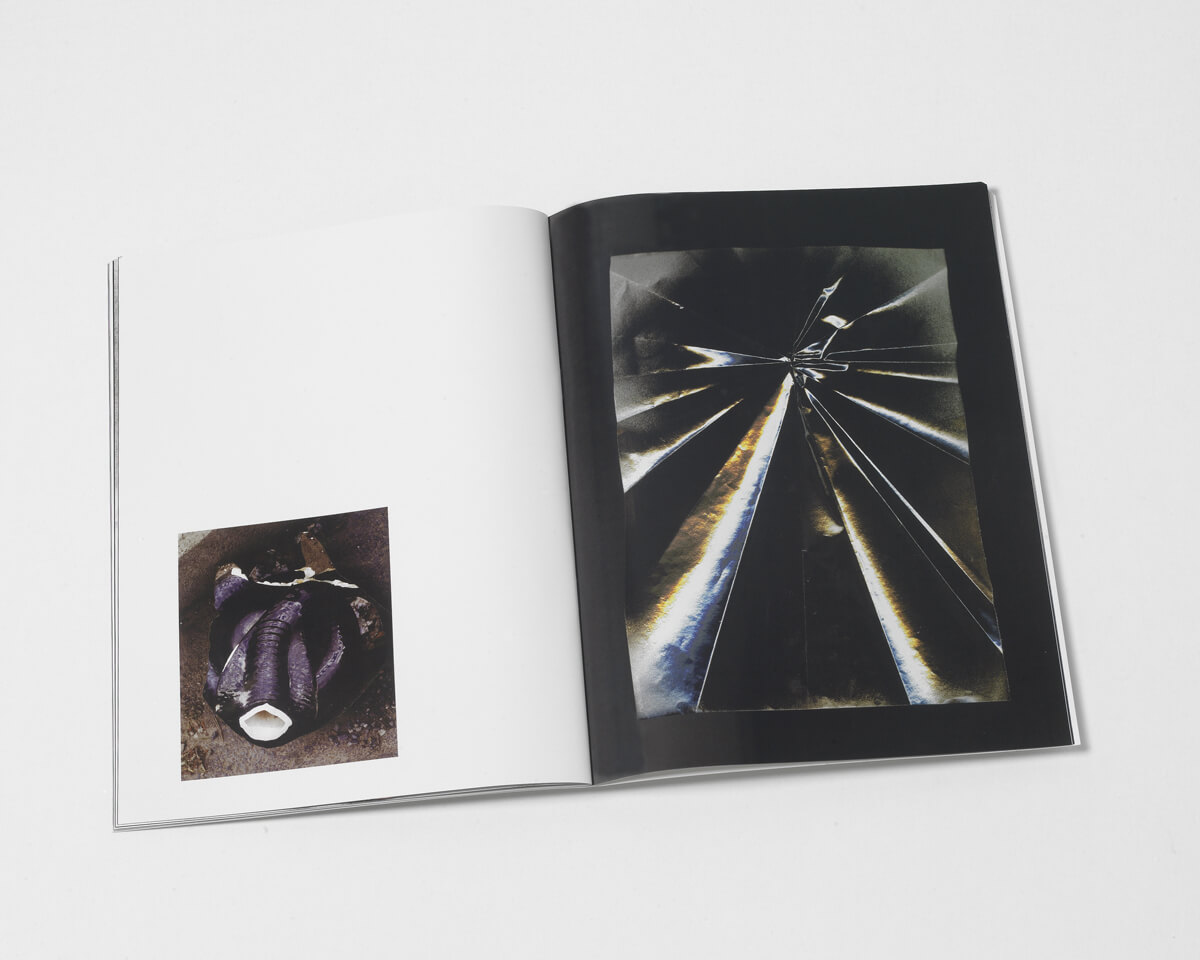

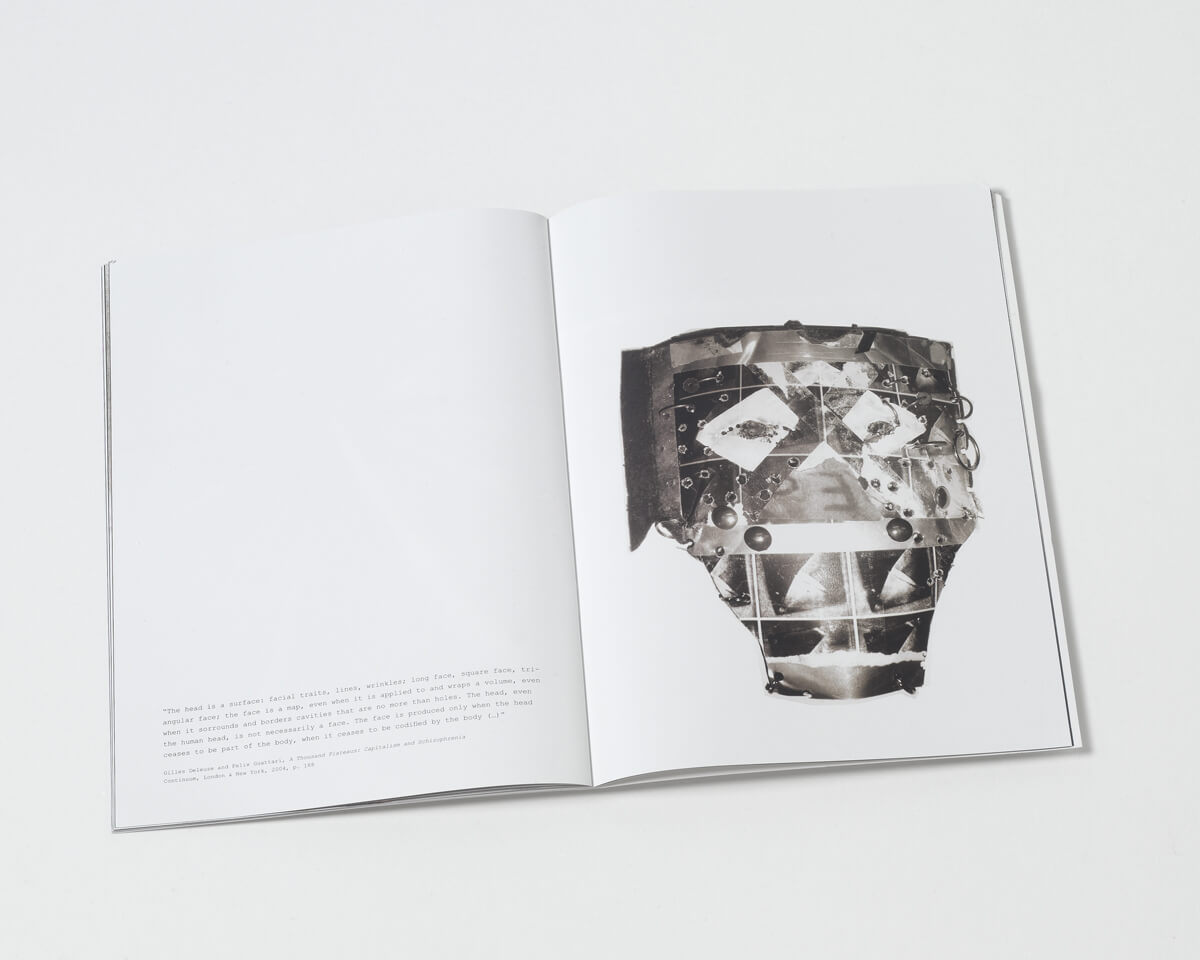

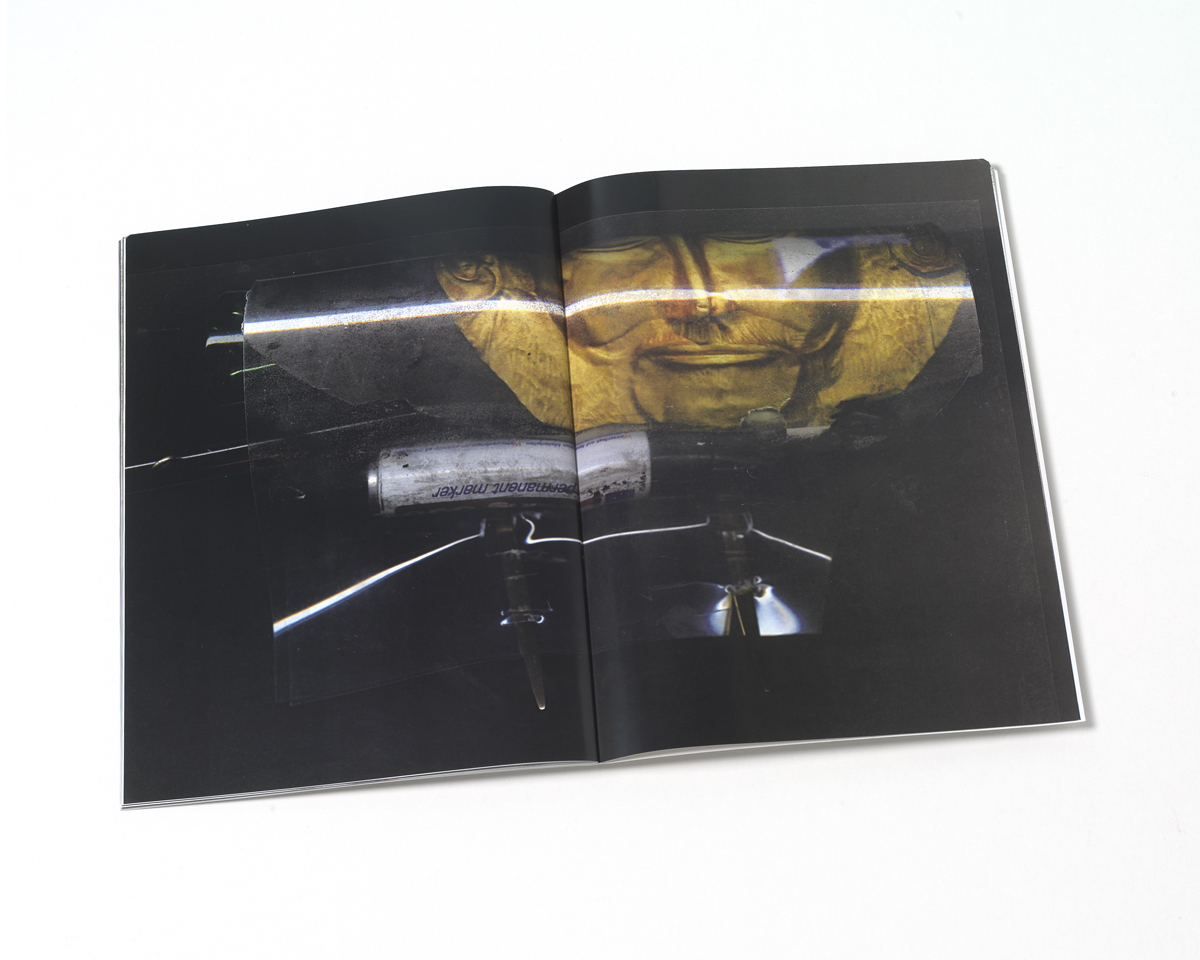

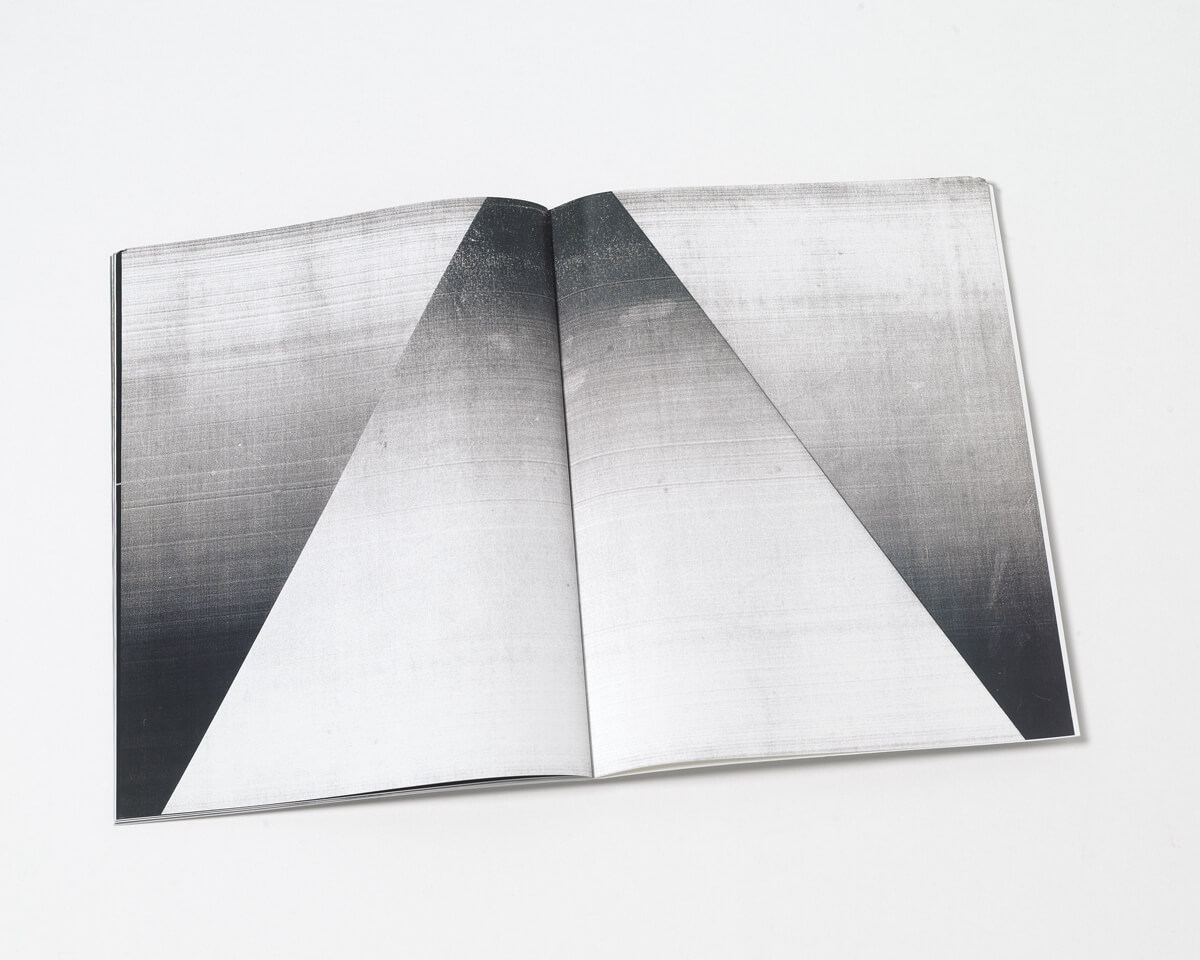

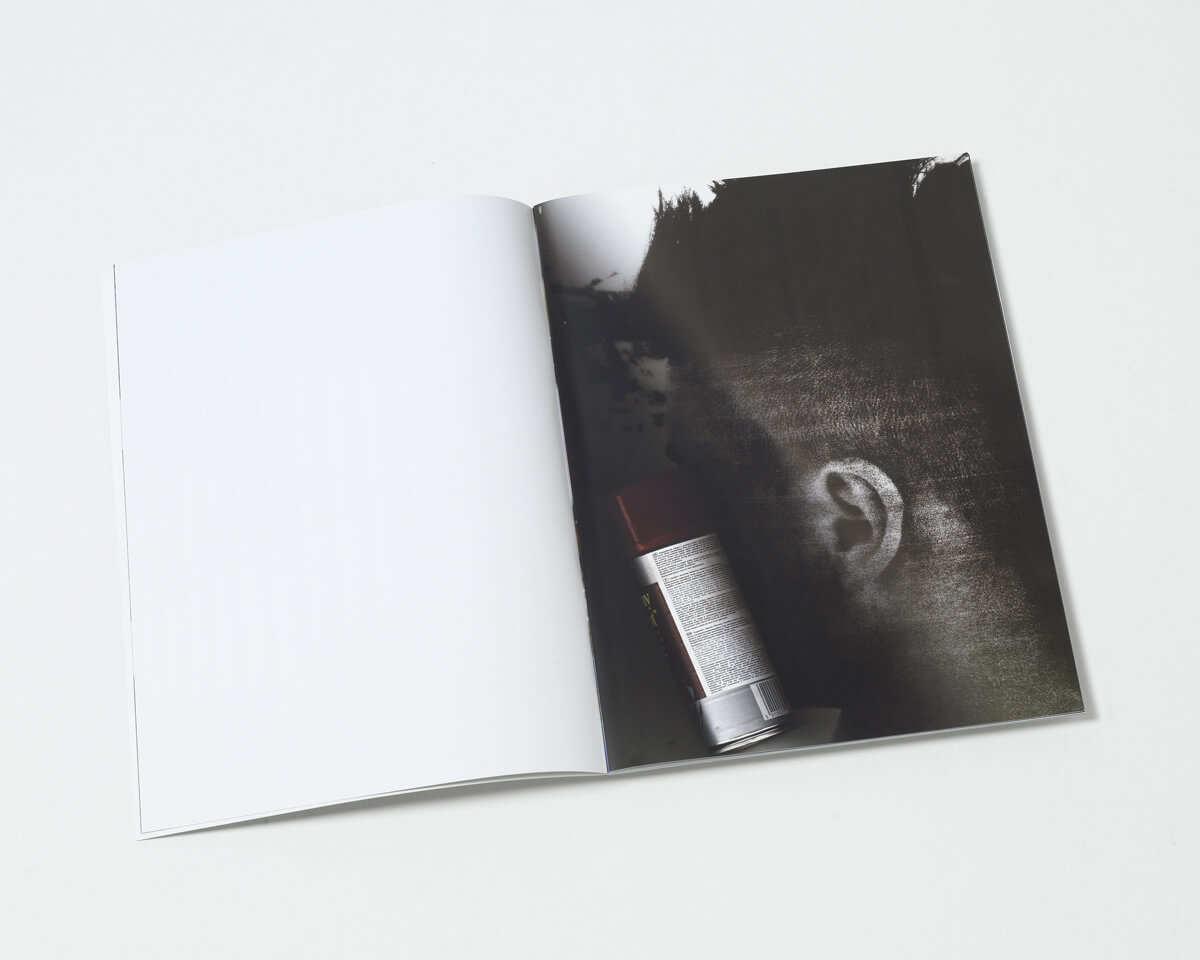

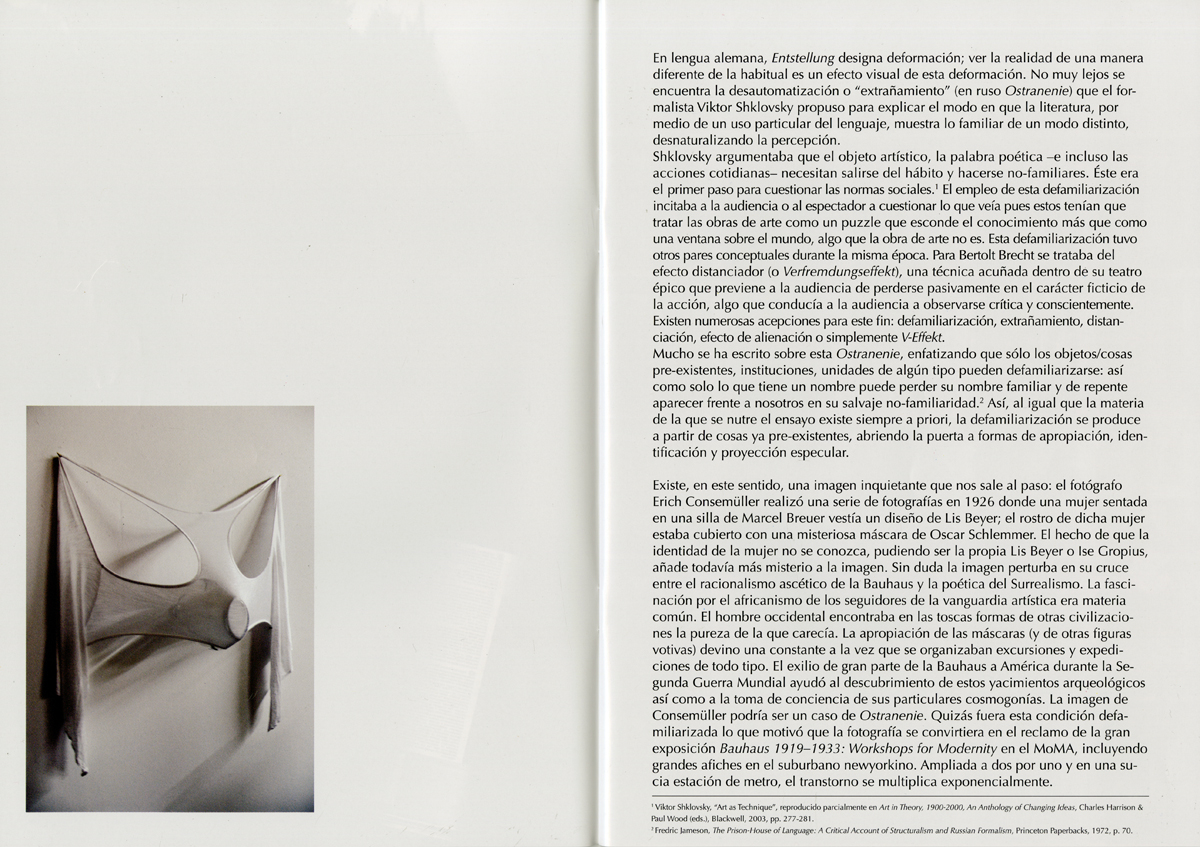

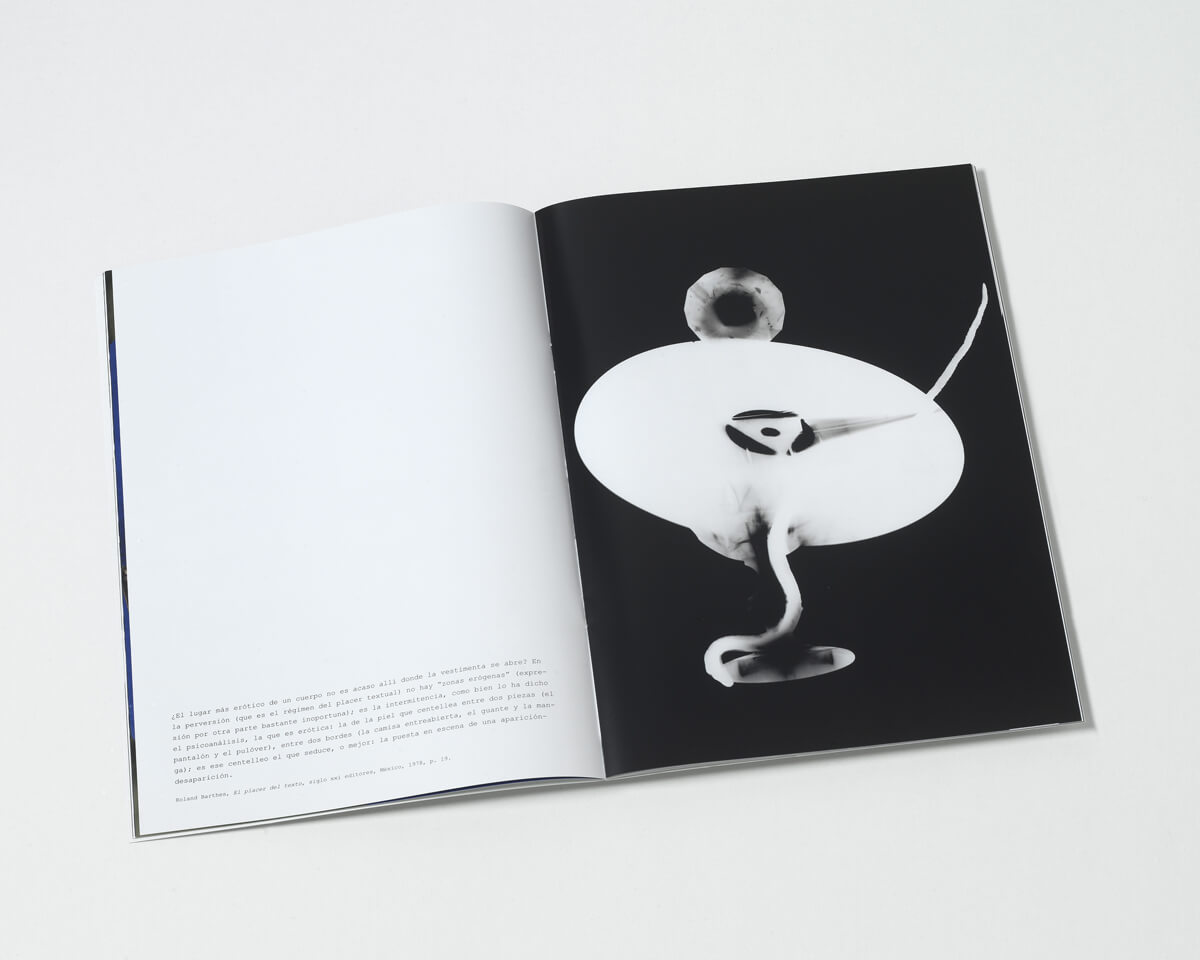

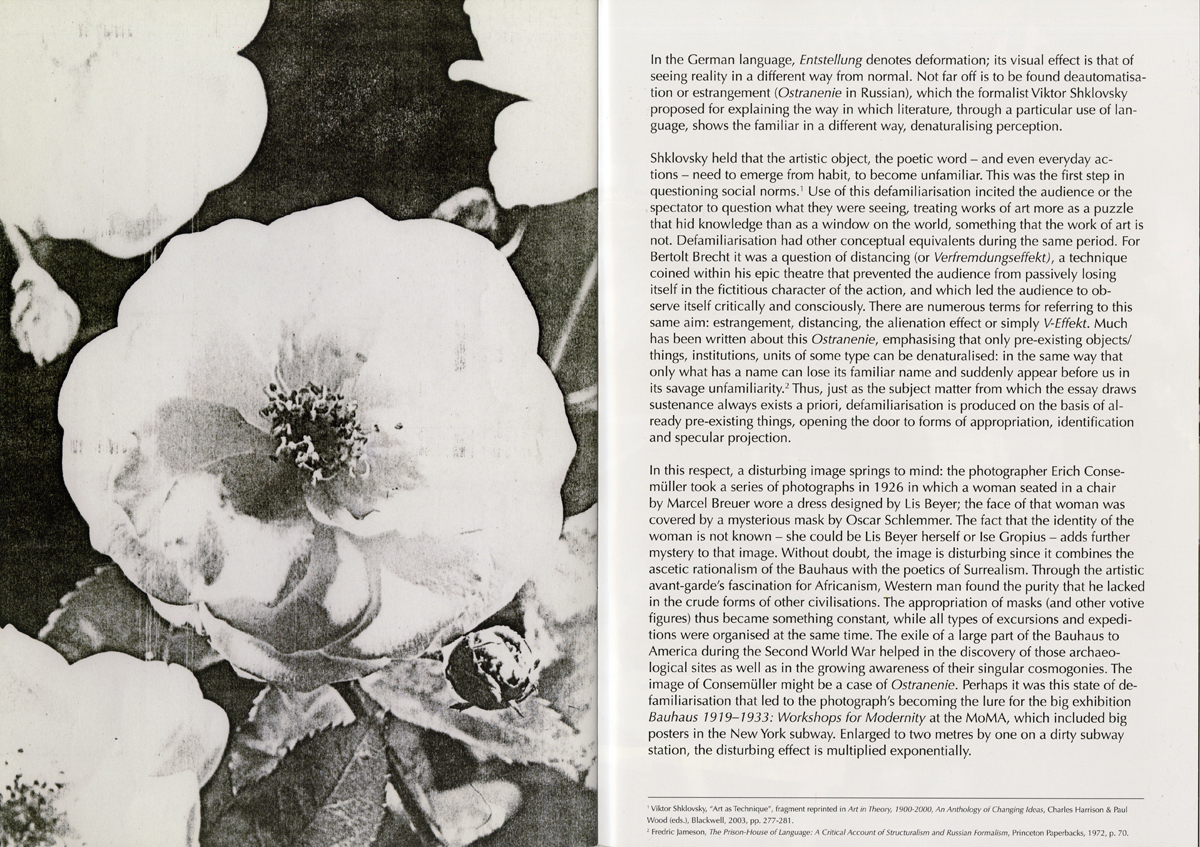

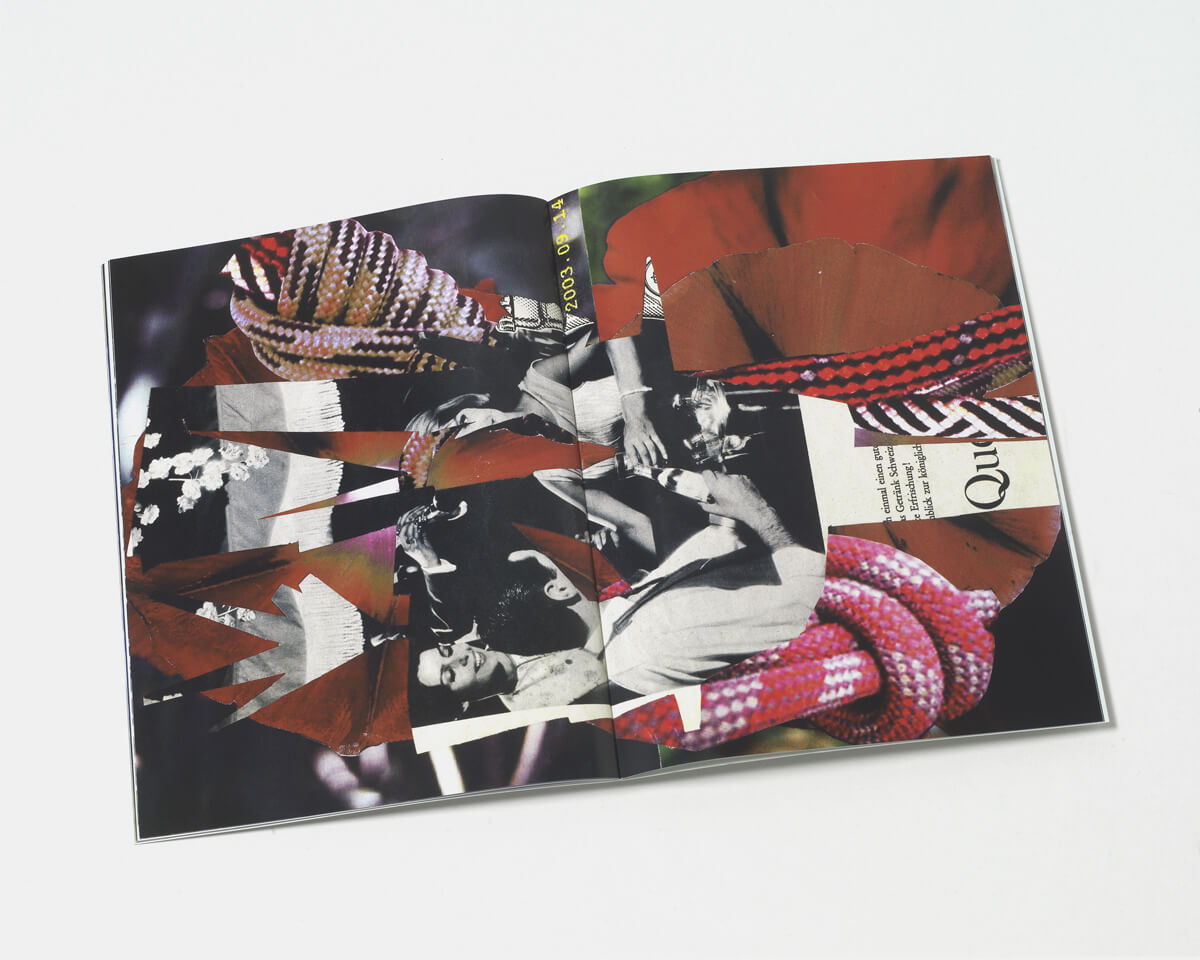

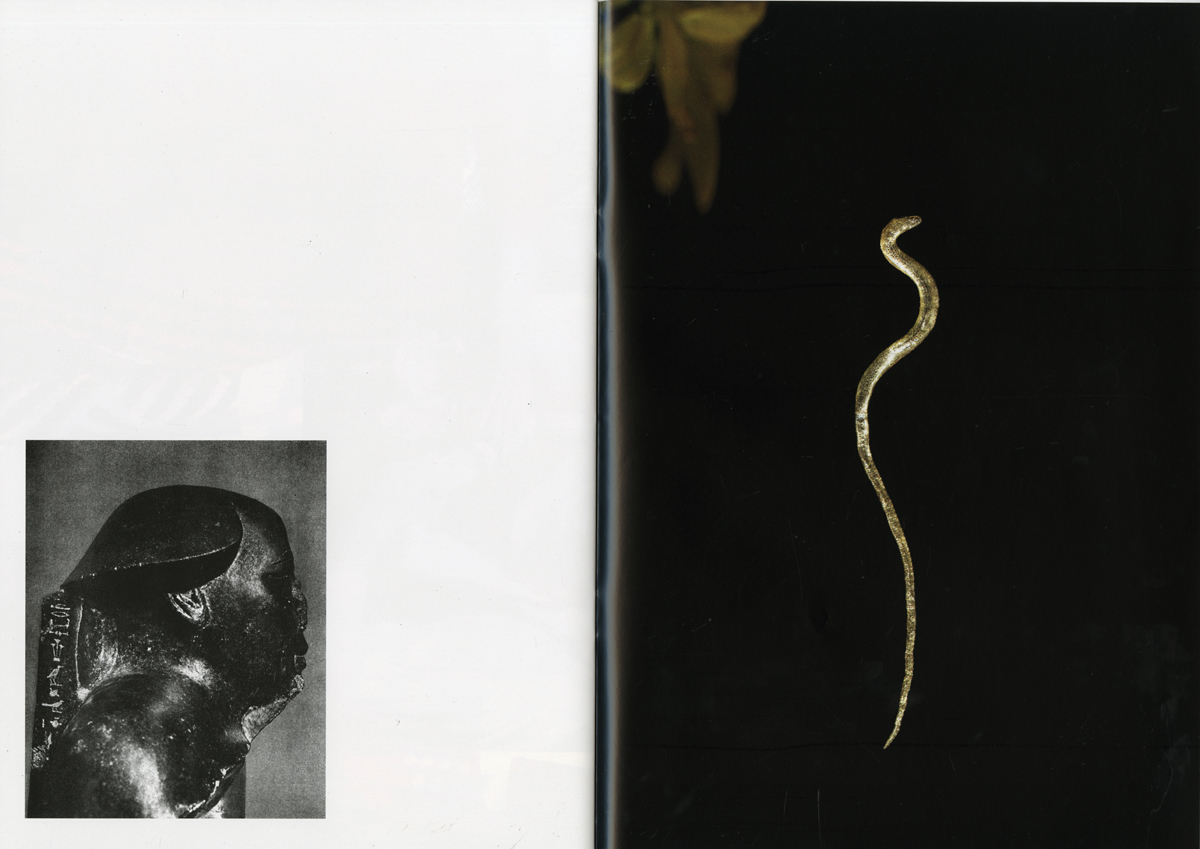

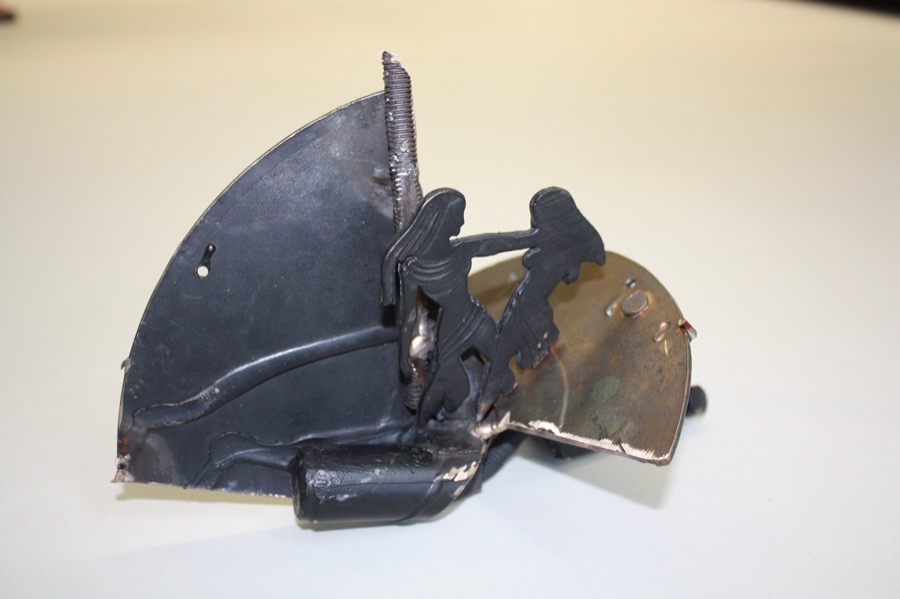

The recent work of June Crespo is not unrelated to this reproductive technique; in her search for personal channels of expression where, in an experimental way, hidden realities emerge that are new and surprising. The association of objects and hidden textures in the most proximate world is inexhaustible. There is a high degree of surrealism in these images, named “scanographs”, which result from the direct scanning of materials and things in singular associations. The evocative potential of these images resides in the seductive and erotic quality of the naked psychodelia of a hard diamond. This surrealist invocation is an instrument in the hands of the artist, where sensitivity and elegance implement form and style. Flowers, hairstyles, felt tip pens, crystals, masks, pendants and textured surfaces are the objects that are transformed into artefacts that, transversally, refer back to avant-garde collages and photomontages (for example to the Dadaist artist Hannah Höch). Equally well-known is the tendency of an art realised by women in which the applied arts, textiles and patterns, as well as a certain “floral art”, take on a gender significance (I am thinking of Isa Genzken or Carol Bove). The orchestrated mise en scène of these objects functions as the esoteric double of reality, embracing the connoted fetishistic powers that surround the narratives on the body, representation and subjectivity.

Peio Aguirre

ES/

Escanografías de June Crespo

La revolución que el descubrimiento de un nuevo avance técnico provoca permanece durante décadas de manera controvertida sin que, por mucho que el paso del tiempo acepte mayoritariamente ese progreso, se disipe del todo la polémica que de forma inaugural amenaza aquello hasta entonces percibido como tradición. La fotografía y el cine son el vivo reflejo de esta situación (a comienzos del siglo XX) en su consideración de nuevas herramientas de expresión para la vanguardia.

Debemos a László Moholy-Nagy el haber empujado los límites del medio fotográfico hacia una nueva existencia. En su libro Pintura, Fotografía, Film, Moholy-Nagy describió el concepto de “fotoplástica”, determinante en la elaboración de sus fotomontajes. Explicaba lo siguiente: “se trata del acoplamiento de diversas fotografías, de una tentativa metódica de representación simultánea: superposición de juego de palabras y visuales; una fusión extraña e inquietante, a nivel imaginario, de los procedimientos imitativos más realistas. Por ellos pueden al mismo tiempo narrar algo, ser sólidos y concretos, más veraces que la misma vida.” Esta ambigüedad entre lo abstracto y lo figurativo lo aplicaba igualmente en sus fotogramas (o fotografías sin negativo) realizados directamente mediante la colocación de objetos cotidianos sobre una superficie emulsionante y su posterior exposición a la luz, inaugurando así nuevos efectos plásticos entre la fotografía y la pintura.

Casi un siglo después, la evolución de la tecnología en la historia y en la modernidad nos previene que la confianza en el progreso no es un cheque en blanco que se entrega por doquier como si de un tranquilizante se tratara. Pero al margen de esto, la reproductibilidad de la imagen técnica no ha dejado de ser la piedra de toque sobre la que artistas de distintas generaciones regresan una y otra vez; de la primera obra conceptual que recurre a la fotocopia (Xerox) de Mel Bochner, Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed As Art (1966), al reciente neo-apropiacionismo ultra-posmoderno de Seth Price o Wade Guyton en su explotación de las posibilidades de las artes gráficas.

La obra reciente de June Crespo no es ajena a esta tecnicidad reproductiva, en su búsqueda de canales personales de expresión donde, de modo experimental, surgen nuevas y sorprendentes realidades ocultas. La asociación de objetos y texturas escondidas en el mundo más inmediato resulta inagotable. Existe un alto grado de surrealismo en estas imágenes, denominadas “escanografías”, y que resultan del escaneado directo de materiales y cosas en singulares asociaciones. El potencial evocador de estas imágenes reside en la cualidad seductora y erótica de la psicodelia desnuda de un diamante duro. Esta invocación surrealista es un instrumento en las manos de la artista, ahí donde la sensibilidad y la elegancia implementan la forma y el estilo. Flores, peinados, rotuladores, cristales, máscaras, colgantes y superficies texturadas son los objetos que se transforman en artefactos que, transversalmente, reenvían a los collages y fotomontajes vanguardistas (por ejemplo la artista dadaista Hannah Höch). Conocida es, igualmente, la tendencia de un arte realizado por mujeres donde las artes aplicadas, los textiles y los patrones (patterns) así como cierto “arte floral” adquieren una significancia de género (pienso en Isa Genzken o en Carol Bove).

La puesta en escena orquestada de estos objetos funciona como el doble esotérico de la realidad, abrazando los poderes fetichistas connotados que rodean los relatos sobre el cuerpo, la representación y la subjetividad.

Peio Aguirre